Imagine you’re working as an Uber driver, committed to working 65 hours a week, and the only other form of income you rely on is from the occasional car repairs you do for neighbors, which only occurs three or four times a month. You have been working extra hours to pay off credit card debt. Unexpectedly, your driver account is deactivated without notice or reason. You attempt to reach a person on the phone to file a complaint, but there’s no answer. Working as an independent contractor, you realize you are left without any of the protections afforded to employees under state, federal, or local laws. You have no retirement plan, health insurance, or money saved for your children’s college tuition. What do you do?

Lack of Protection From Misclassification

The lack of protection illustrated above rests on the fact that official organizations, such as the Department of Labor, acknowledge that Uber classifies its drivers as independent contractors, not employees. This classification applies to drivers whether they work 3 hours a week or 60 hours a week. How does this make sense? It doesn’t! This has been an ever-growing issue for drivers who seek employment protections and for companies, such as Uber, that argue it is financially unconscionable to require them to spend millions of dollars on employment benefits for drivers who may only work a few hours a week.

Uber is just one of the many “gig economy” companies that struggle to remedy the tension between the interests of workers and those of the corporation. In fact, “gig economy” companies constitute only one portion of companies that are alleged to misclassify their workers as independent contractors. A rising debate in the media has focused on gig/digital platform companies, yet the misclassification occurs across all sectors of the economy, affecting millions of workers every day.

The Transforming Nature of Employment

The attention to this issue of misclassification arose as a result of the explosive employment transformation from “traditional, full-time employment” to “alternative, contingent work arrangements” that has led to our nation’s “gig economy.” This rising trend is a result of “electronically mediated work” via online platforms that allow workers to connect with consumers, get paid instantly, choose when and whether to work with just a push of a button, and carry out short or long tasks in person or online. Workers yearn for this job flexibility, yet what is missing is a system that will account for those relying on their jobs as more than just a “side gig.” We must find a way to balance the efficiency of the labor market with the fair treatment of workers.

Many companies were built on business models that relied on and continue to rely on cost-cutting strategies, including the ability to hire workers as independent contractors to avoid employer liability and the financial obligations, such as employment benefits and minimum wage, that come with characterizing workers as employees under federal and state law. The Fair Labor Standards Act, a federal law granting protections to employees, does not provide any protection to independent contractors and does not define what exactly an independent contractor is. The lack of guidance in the Act runs contrary to its very purpose, which is to provide an inclusive federal baseline for employee classification that will protect the health, safety, and welfare of workers. As a result of the lack of clarity under the FLSA regarding the distinction between independent contractors and employees, many hiring entities are intentionally misclassifying certain workers to avoid the financial obligations that come with an employee classification.

Legislative Response to the “Gig Economy”

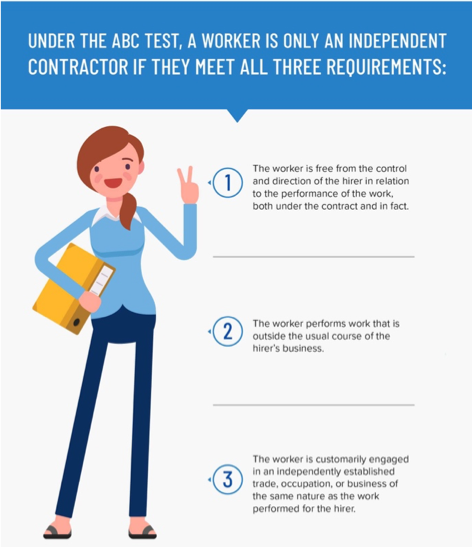

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, gig businesses make up a multibillion dollar sector of the economy and rely on workers who are anticipated to make up 43% of the entire workforce by 2020. This sudden, rising change towards gig work has caused many states to take on these issues themselves, drafting their own protective legislation. For over 30 years California has strived to perfect a standard defining what type of worker should be classified as an independent contractor. Using precedent from the California Supreme Court’s 1989 decision in Borello & Sons v. Dep’t of Indus. Relations and its 2018 decision in Dynamex Operations v. Superior Court, the California legislature in September 2019 signed into legislation “Assembly Bill No. 5” (“AB5”), which codified the “ABC” test formulated by the California Supreme Court in Dynamex. The “ABC” test defines what an independent contractor is.

Improving California’s Legislation

However, California’s AB5 should be modified. The standard is unpredictable and ambiguous, and, as a result, it opens the door for loopholes and continued misclassification by corporations that manipulate the language of the bill to fit their needs. Additionally, AB5 dedicates an entire paragraph to exempting certain occupations from its reach. To enhance predictability as the employment market continues to change and grow, there should be no exceptions.

The three parts of the “ABC” test need to be clarified. Part A of the test should include the following language: a hiring entity does not have to control the material details of the work, those being details that can only be done in one way or that do not require any particular skill beyond that expected of an employee. This language is necessary to account for instances in which an employer need not control and direct all aspects of an employee’s work. For instance, Uber may argue it does not control the driver’s performance at all times and, so, should not be deemed an employer under this prong. However, when there is generally only one way to complete a task, such as driving from Point A to Point B, supervision through Uber’s app rating system can suffice to monitor the driver’s performance and behavior without the unnecessary need for Uber to have an in-person supervisor for each driver.

Second, Part B of the test needs language clarifying what work outside the “usual course of the hiring entity’s business” means, specifically whether the hiring entity’s business is conceivable without the service provided by the worker. This addition will account for the work that does not always fit neatly into what a company determines its usual course of business to be. For example, many gig economy companies, such as Uber, characterize themselves as technology companies. Therefore, they argue drivers are not integral to their core operation as technology companies and deny accusations they are transportation companies. To avoid such attempts to evade employer classification under Part B of this test through the use of “semantic distinctions,” additional language to this prong is required.

Lastly, Part C needs language specifying that when a worker is engaged in an independently established trade, he or she has independently made the decision to go into business for himself or herself. This additional language comes from the California Supreme Court’s definition of independent contractor. The current language does not indicate any willful choice on behalf of the worker to engage in a particular trade, occupation, or business. Therefore, clarifying that working in a particular trade was a result of a worker’s cognizant decision to do so is necessary to avoid any abuse by hiring entities who may unilaterally determine its workers engage in a particular work without any evidence it was the worker’s choice to do so.

Although AB5 is “arguably the strongest bill of its kind,” the bill must be taken a step further as a way to more effectively carry out the very purpose for having protective labor legislation in the first place. The current test fails to capture the difference between workers who seek the freedom and flexibility of independent contracting and those who yearn for the reliability, consistency, and protection of working as an employee.